How Bad Do You Want It? - Part 1

The fine line between someone successful and someone trying to be is ...

The fine line between someone successful and someone trying to be is the willingness to sit in the discomfort of doing a little bit more than most.

I wrote that down in my Notes app one night when I was contemplating life, specifically, why I insist on pushing myself to do the 30-minute treadmill walk instead of stopping at exactly 20 or even 25. No one’s watching. There’s no reward.

People love to debate whether success comes down to natural talent or effort, as if it’s some philosophical toss-up. In reality, it’s both. And effort, unlike talent, tends to show up when it’s least convenient.

Take international students in the U.S. You can’t just get a job by filling in a Workday application. You have to clear regulatory hoops and file half a forest’s worth of paperwork. One of those hoops is a CPT form1, which means enrolling in a required summer course (expensive, inconvenient, and soul-draining), logging 150 to 300 hours of work for a mere 3 credits, and participating in weekly modules on goal-setting, career planning, and testing that elusive quality everyone suddenly cares about: grit.

HR eats that buzzword up like it’s a TED Talk protein bar.

Normally, I’d half-listen to the self-paced modules and outsource the rest to ChatGPT. But lately, I’ve had less tolerance for coasting. Something about the friction is starting to feel necessary.

In one of our readings, I learned about West Point2 - the kind of place where even varsity team captains are considered average. Each year, over 14,000 high school juniors apply. Only 4,000 get nominations. Fewer than 1,300 make it through. And even then, one in five will still not graduate.

Many drop out during the first seven weeks, during a program called Beast Barracks, or simply Beast. It's exactly what it sounds like: physically brutal, emotionally isolating, and intentionally designed to push people past their breaking point.

A Typical Day at Beast Barracks

5:00 a.m. Wake-up

5:30 a.m. Reveille Formation

5:30 to 6:55 a.m. Physical Training

6:55 to 7:25 a.m. Personal Maintenance

7:30 to 8:15 a.m. Breakfast

8:30 to 12:45 p.m. Training/Classes

1:00 to 1:45 p.m. Lunch

2:00 to 3:45 p.m. Training/Classes

4:00 to 5:30 p.m. Organized Athletics

5:30 to 5:55 p.m. Personal Maintenance

6:00 to 6:45 p.m. Dinner

7:00 to 9:00 p.m. Training/Classes

9:00 to 10:00 p.m. Commander’s Time

10:00 p.m. Taps

No weekends. No breaks. No calls home. Just a loop of stress and repetition.

So, who makes it through Beast?

Mike Matthews, a psychologist and longtime West Point professor, studied who actually survives Beast. The admissions team had already built a scoring system called the Whole Candidate Score that factored in everything from SATs to leadership credentials. In theory, it should’ve predicted success.

Well, short story long…

It didn’t.

Cadets with the highest scores were just as likely to drop out as those scraping the bottom. Which made Mike think: what if we’re measuring the wrong thing?

At the same time, I was coffee-chatting with high performers across industries - CEOs, CFOs, athletes, artists, lawyers. They all described success in different terms.

A hedge fund manager described success as a tolerance for high-stakes decisions: “You’ve got to make million-dollar calls and still sleep, eat, play, repeat.” Bakers, on the other hand, talked about creation for its own sake: “I like making things. I don’t know why - I just do and I’m good at it.” Meanwhile, bodybuilders framed it differently altogether. For them, it was about competition: “Winners live for the head-to-head. They don’t just want to win - they want to embody the best.”

Across all these conversations, the details changed, but the patterns didn’t. Yes, the top performers were talented. Some had luck on their side, too. Is it really that surprising?

What caught my attention, though, were the stories of the ones who didn’t make it. The rising stars who, for no obvious reason, dropped off the radar. Not because they weren’t smart enough or skilled enough, but because they lost momentum.

Turns out, talent doesn’t guarantee staying power. Some people are great when things are going well, but they fall apart when things aren’t.

As a young airman, Matthews had been through something similar. The first weeks broke people, not their bodies, but their will. The ones who stayed weren’t necessarily the smartest or the strongest. They were the ones who kept showing up. It was tolerance for failure, for discomfort, for things not going as planned. The ones who experimented, adjusted, and tried again. They didn’t settle in the soft gray of “It’s the thought that counts.”

I grew up with a mother who made it very clear: it’s never the thought that counts. Not really. What counts is the result. If it is tangible, even better. Something you can point to and say, “This is what I did.” Effort only mattered if it translated into something real - proof of your sweat or tears.

I’m being dramatic, but you know what I mean.

Anyways, I learned that the hard way. For her birthday, I spent weeks saving money from a tiny catering business I ran for classmates at sixteen. A little scam artist, I charged them Rp. 100,000 per bowl - twice the market rate. I used the money to buy what I believed were the most beautiful, colorful flowers known to mankind. When they arrived, she smiled, said thank you, and moved on. What I thought was heartfelt, she found mismatched. She’s always been a pink roses kind of lady - not red, not white, and definitely not rainbow. To be very fair, tie-dye was in back then and very much hot girl Tumblr.

I had given her what I thought was beautiful. But I hadn’t really seen her.

And while some people might say, “Geez, what kind of household is that?” I’m grateful for it.

That tough love gave me thick skin. It taught me to stop settling for (in)significant others who didn’t deserve me, for friends who only took. It made me unafraid of confrontation and unshaken by harsh feedback. I don’t flinch when someone tells me I missed the mark. I just go back, fix it, and try again. That’s what my mom taught me: stop taking things personally, deliver what matters, not just what feels meaningful to you. Make it land.

I didn’t shut down when I got my feelings hurt. I shifted and understood my mother better. And that kind of perspective, fortunately, can’t be taught by talent. It’s persistence with no guarantee. It’s showing up anyway.

The people who don’t burn out or bail all seem to have this stubborn, restless hunger. They’re not chasing trophies. They’re wrestling with their own self-ambition. And the strangest part? They never feel satisfied. They’re always reaching. Always a little discontent and somehow, content being discontent.

Over time, I realized it came down to two traits: resilience and focus. The people who got far weren’t just aimlessly determined. They knew what they wanted and tried hard on purpose. That combination of sustained effort and clear intention is what we now call grit.

So the question became: how do you actually measure something like that? Something invisible but deeply felt? Something every overachiever claims to spot “instinctively,” but that no one seems to know how to quantify?

I started small, just writing down the kinds of things gritty people said about themselves. Some questions focused on perseverance:

– I stick with goals even when progress is slow, sometimes invisible.

– I make new resolutions each year.

– I finish what I start.

Others were about the consistency of interest:

– I’ve stayed committed to the same passion for years.

– I don’t jump from idea to idea without follow-through.

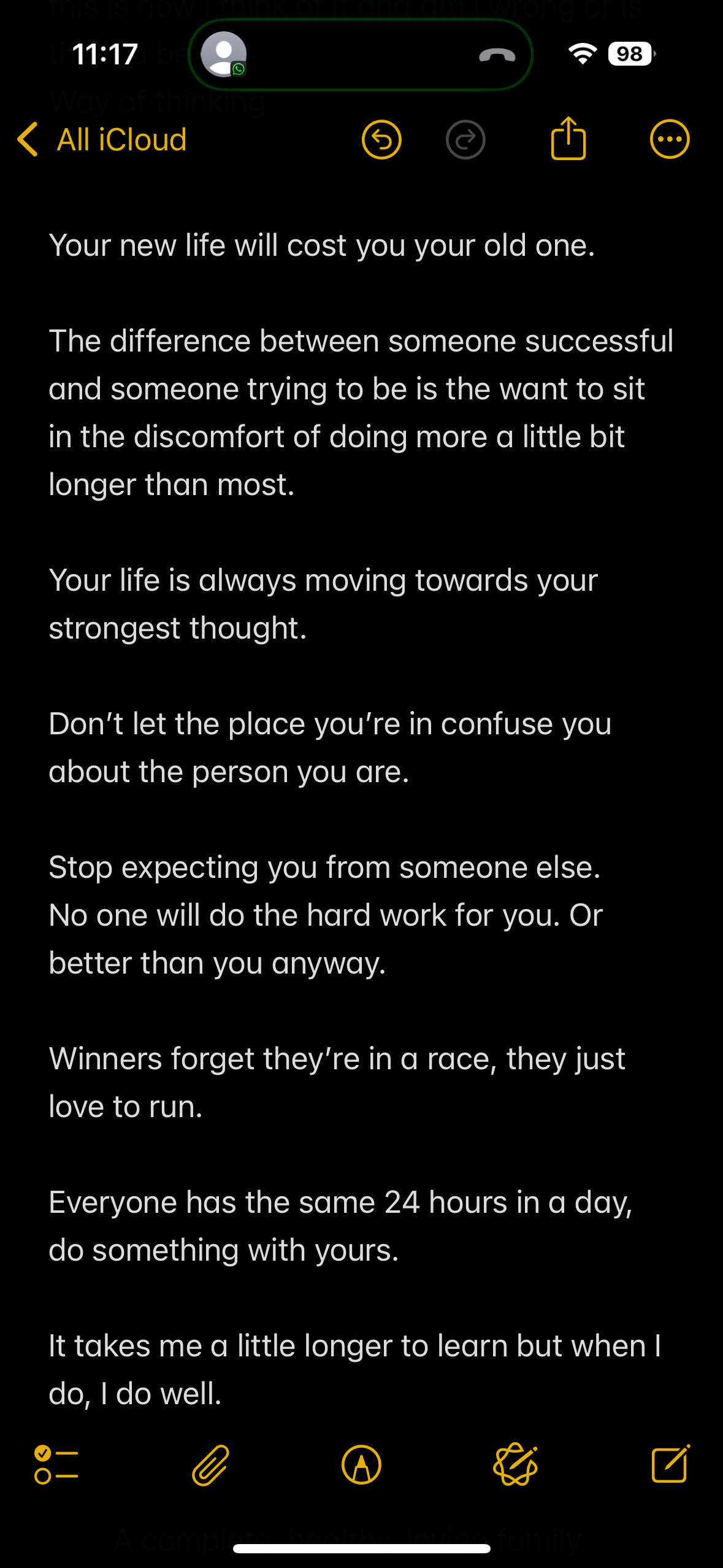

And soon after, my notes became a reservoir of words that helped me push through. Here’s some I’d like to share with you:

And that’s how the Grit Scale came to be. Not as a perfect metric, but as a structured attempt to capture the mindset behind long-haul effort.

In 2004, 1,218 cadets at West Point took it.3 This was during Beast - their notoriously brutal seven-week initiation. They’d just said goodbye to their parents (West Point allotted exactly 90 seconds for that), shaved their heads, changed into uniform, and received a year’s worth of gear and pressure.

What we found was telling. Grit scores had no correlation to the official West Point admissions ranking - the Whole Candidate Score, which weighs academics, athletics, leadership, and fitness. You’d think the high scorers would be more likely to survive the Beast. They weren’t.

What predicted endurance wasn’t talent. It wasn’t high SATs or perfect GPAs. It was grit.

By the end of the program, 71 cadets had dropped. But their academic and fitness credentials? Basically identical to the ones who stayed. The usual metrics said nothing.

Which raised the bigger question: does grit matter outside West Point?

Francis Galton, a Victorian child prodigy who collected geniuses like Popmart blind boxes4, tried to pin it down. He was six when he picked up Latin, nailed long division, and memorized Shakespeare.

His half-cousin, Charles Darwin, wrote to him, somewhat amused. “You have made a convert of an opponent in one sense,” wrote Darwin. “For I have always maintained that, excepting fools, men did not differ much in intellect, only in zeal and hard work; and I still think this is an important difference.”5

Darwin himself didn’t think of his mind as particularly fast or gifted. He wasn’t the type to solve problems in a flash or memorize poetry for fun. But he was relentless. He observed everything. He followed questions he didn’t know the answer to long past the point where most people would’ve shrugged and moved on or forgotten.

He called it “plodding.” I call it proof that you don’t need to be effortlessly shrewd - you just need to keep showing up.

One of his biographers noted how he never really let go of a puzzle. Even when it sat dormant in his mind, he kept it there, waiting, watching. He didn’t forget the hard stuff. He circled back to it.

Most of us don’t do that. We let friction talk us out of things. We start projects, lose steam, and convince ourselves we’ll come back to them later (we rarely do). We aim for effort but settle for distraction.

And that’s the part I keep coming back to.

Compared to what we’re capable of, we barely scratch the surface. We move through the world half-asleep, conserving energy we’re not even sure how to use.

I’ve said it before in another blog post - maybe too often - but I don’t think I’ve ever done anything at full capacity.

Lately, I’ve been wondering what would happen if I tried.

Bye,

Felicia

CPT (Curricular Practical Training) is a type of work authorization that allows international students in the U.S. to gain off-campus employment experience directly tied to their field of study. It often requires course enrollment and school approval.

West Point refers to the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York - not to be confused with unrelated locations or organizations in other states.

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (Grit–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

Pop Mart blind boxes are collectible toys sold in sealed packaging, popular for the surprise element - buyers don’t know which character they’re getting until they open the box. One of the most beloved characters is Labubu, a mischievous gremlin-like creature with a cult following.

Angela Duckworth, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance (New York: Scribner, 2016).